|

Analytics

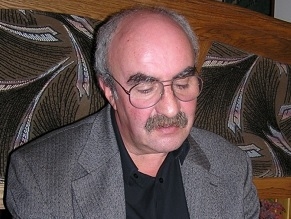

Moisei Fishbein

|

A Failed Redemption and Its Deceased Messiah: The Loss of Moisei Fishbein (December 1, 1946-May 26, 2020)

03.06.2020 Moisei Fishbein considered himself a Ukrainian Messiah (In Ukrainian, "Moisei" means Moses), and his return from exile to Ukraine—an advent. He returned from exile twenty years ago to fulfill his lofty mission: to redeem the Ukrainian language from Russification, assimilation, and deprecation. Moisei, a Chernivtsi-born Jew, portrayed himself as the protector and savior of the humiliated, raped, and sacred Ukrainian language.

On May 26, 2020, the Ukrainian Messiah Moisei Fishbein passed away. Very few people understood what had happened and even fewer bemoaned it. Moisei walked the streets of Chernivtsi, Novosibirsk, Odessa, Jerusalem, Munich, and Kyiv, but in fact he belonged to another realm. There, in that other realm, he saw Taras Shevchenko in his dreams and saw the dreams of Shevchenko. He spoke to Lesya Ukrayinka as a prophet to a prophetess. In that realm, Mykola Bazhan blessed his talents, compared him to the “talented and sorrowful” Yevhen Pluzhnyk, and propelled him into the Ukrainian literary milieu. And in that sublime realm, Leonid Pervomais’kyi told Fishbein, “You do not know anything yet, you do not know,” hinting at the passions Fishbein would soon have to face.

Fishbein’s Via Dolorosa began the moment he, a student of cybernetics at Novosibirsk University, switched from Russian verse to Ukrainian and decided to become a Ukrainian poet. He followed in the path of Leonid Kyseliov and prefigured that of Borys Khersons’kyi. With all his early messianic fervor, he was neither arrested nor imprisoned, and his time in a special military construction battalion in the Far East was perhaps the worst episode in his personal experience, except for his exile. For a Ukrainian poet, Soviet army service in the Far East, university studies in Novosibirsk, living in Altenerding and working in Munich for Radio Liberty/Free Europe (“brekhalivka,” as he called it, from Ukrainian "brekhaty", "to lie') and even living in Jerusalem was bitter exile.

Exile meant silence. Yes, he produced work: he translated Maximilian Voloshyn at the request of the Ukrainian philologist George Shevelov (Yurii Sheveliov). Ihor Kachurovs’kyi, one of the top Ukrainian translators of the 20th century, commissioned him to compose a bouts-rimés for his monograph on versification. For Israel Kleiner, a Ukrainian Jewish dissident and émigré journalist, Fishbein translated excerpts from Vladimir Jabotinsky’s works. “Besides this, I did not write anything,” Fishbein explained. “They asked me, ‘Why?’ I answered, ‘What for? Who needs it? Who will see it in Ukraine?’ Only when the early dawn had just risen in Ukraine, Bohdan Boychuk told me, ‘Moisei, write. Your poetry will reach Ukraine.’”

Fishbein answered the challenge. Early in February 1989, in Germany, he wrote his programmatic poem that rhymes Kyiv with Jerusalem, the Jordan with the Dnieper rivers, the Western Wall with the spring hills of Kyiv—Ukrainians with Jews, Ukraine with the land of Israel.

…A mouth contorted in pain,

And an immortal soul has taken on

The scorched hills of Jerusalem

And Kyiv’s burned over greenery.

O droplet, glimmer, bumblebee,

Little pearl, destiny, you half-invisible

Intangible rhyme of my existence,

Its sting, red-hot and sweet—

Bless these things, to be my own—

Fog falling over the Wailing Wall

And spring falling over the Dnieper.

Bless these things, to stay my own

As long as I walk in the world,

As long as I can still remember.

Trans. by Bohdan Boychuk and J. Kates

That symbiosis was and remained his hope, his prayer, his faith. It brought him back to Ukraine. He returned on the eve of the Orange Revolution, which for him became a personal apotheosis—and, subsequently, a disaster. Fishbein found himself among the proponents of the Ukrainian irredenta, peaceful and non-violent but emphatically anti-imperial. As a succinct prophet with an unforgettable low voice and irresistible Ukrainian, he was co-opted by the Orange Revolution leaders, who did not deserve his messianic drive.

The Orange Revolution spun Fishbein to the fulcrum of the events. We can certainly understand what he went through. Byron was never able to enter Athens victoriously liberated from the Turks, Mickiewicz did not have a chance to raise the Polish flag over the barricades of Warsaw in 1863, and Lesia Ukrayinka did not live to see the attempts of the Central Rada to establish an independent Ukrainian polity. Indeed, they were also spared from seeing the disastrous ramifications of those upheavals.

What did not happen for Byron, Mickiewicz, and Lesia Ukrayinka, however, became possible for Fishbein. The events of December 2004 brought him to Maidan and raised him onto the tribune from which the putative leaders of the Orange Revolution spoke to hundreds of thousands protesters and millions of people nationwide. Recovering from a recent stroke, Fishbein spent several days picketing on the Kyiv streets in wintry weather. He was confident that his prophecies had come true. He was overwhelmed by the hundreds of thousands of people surrounding him in Kyiv, by the several-week-long suspense while the incumbent president tried to remain in power, by the atmosphere of solidarity of people of different creeds, political ambitions, ethnic groups, and by the unusually friendly atmosphere in Kyiv.

The eve of that misunderstood, abrupt, and forgotten revolution saw Fishbein actively campaigning in favor of opposition candidate Viktor Yushchenko, then the leader of the “Our Ukraine” block. Fishbein supported him not only because Yushchenko’s family in the Sumy District village intelligentsia had saved Jews during the Holocaust, but also because Yushchenko’s stance on Ukrainian revivalism fit with Fishbein’s own redemptive scenarios for the Ukrainian language and culture. Addressing his fellow Jews on the pages of one of the most influential Ukrainian-Jewish newspapers, Fishbein ignored Yushchenko’s political impotence and instead portrayed him as a tolerant politician favoring Ukrainian-Jewish rapprochement. He courageously called on the Jews of Ukraine, in most cases Russian-speaking, conservative, and Yanukovych-supporting, to vote for Yushchenko, for genuine Ukrainian independence, for Ukrainian revivalism, and against Russian intrusion into Ukrainian affairs. “Ukraine should not be an amorphous segment of the post-communist state labeled ‘the Ukraine,’” argued Fishbein. “Rather it should be the Ukrainian Ukraine as France is French and Germany is German.”

Back then, politics did not change Fishbein’s firm rejection of cheap publicity and handsome honoraria. Though his financial conditions were rapidly deteriorating and his living conditions awful (in 2003–2005, he lived in a tiny one-room apartment with his distant relatives), Fishbein never lost his charisma, aristocratic bearing, and stamina. He would not collaborate with proponents of new forms of Ukrainian colonialism. When one of the most popular TV programs on the pro-government channel suggested that Fishbein sit for a lengthy interview, he refused. He did not want to have anything to do with TV journalists servile to the corrupt pro-Russian politicians. “Let them know,” he told me, that “it is as likely for Fishbein to appear on Medvedchuk’s TV channel as on the pages of the Völkischer Beobachter.” The latter of course, along with Der Stürmer, was the main Nazi newspaper.

Fishbein felt not only home again: his home had become what Fishbein wanted it to become. He had never been as happy as then, never before and never since. What he saw changed his notoriously deficient social skills: Fishbein sought out and found dozens of fellow thinkers and interlocutors. Early in the fall of 2004, Fishbein befriended Yaroslav Lesiuk, a former psychiatrist who designed the orange ribbon, subsequently the revolutionary symbol. Fishbein remembered a popular Russian children’s song, “Oranzhevoe nebo” (Orange Sky), which had mass popularity in the 1970s. It was the story of a little girl drawing an orange world around her, painting herself in orange, her mother singing orange songs, and arguing with a gloomy guy who disapproved of her optimistic worldview as unrealistic. But once the sun came out, the song went, the world became orange through and through, surprising the rationally-minded guy, a skeptic, and unbelieving bore. Why not use this apparently innocuous children’s song for political purposes? Why not take a Russian song written by two Jews and make it serve the Ukrainian people? Fishbein made a number of calls to various radio stations that take requests, and before the first round of Ukrainian elections, several million people had listened daily on the radio to the children’s song that became a charming anthem of the “orange” democratic opposition. Fishbein thoroughly enjoyed his undertaking.

Here is Fishbein pondering this story in the midst of the unfolding revolutionary events in November 2004:

Orange is everywhere. I put on my T-shirt and an orange stripe. People fix orange to the trees in town: the whole city is covered with them! I don’t know who managed to climb to the top of the Column of Independence in the central square of the city and place a huge orange flag there with the inscription “Yushchenko!” It is illuminated from below and at night, when the wind stirs it, it creates a fantastic, unbelievable impression—an enormous orange flag unwinding over the city. “Gangsters” [supporters of the incumbent candidate Yanukovych] started to hit and slash the tires of cars of Kyivans that are orange—poor fools, do they think that by doing this they will stop people from voting for Yushchenko? There is not a strip of orange fabric in Kyiv stores: everything has been sold out.

Once Viktor Yanukovych (today a runaway politician hiding in Russia) was announced the winner and hundreds of thousands of bewildered people streamed into the streets of Kyiv, Fishbein joined the protesters. He spent the whole week after the November election on the Maidan, sleeping just a few hours and rushing back from the left bank district of the capital to the city center. “Thank God I am not elsewhere, but here in Kyiv. I would not forgive myself if I were anywhere else,” he said. Despite the enormous tension of the events underway and his poor health, Fishbein was proud of participating in the events, even though it could have cost him dearly. Still, he claimed, “It’s a pity I returned only a year ago. Had I returned earlier, perhaps I would have avoided a stroke.” His personal contribution to the revolutionary events went beyond popular chants.

Fishbein’s observations in the fall of 2004 crystallized the sense of a birth of a new Ukrainian nation that many Western observers and citizens of Ukraine experienced in the streets of Kyiv. What makes Fishbein’s observations distinct is his intent to observe the events intimately without losing perspective and a sense of the background, with its ignominious “gangsters,” the clique of oligarchs, the corrupt Kuchma, the ignominious prime minister Yanukovych, and simultaneously integrating them into a broader vision of the post-colonial country. Indeed, his experience provided him with the most important conclusion he would make: that the Orange Revolution put an end to Ukrainians as voiceless and docile. It signified the birth of a new multi-ethnic, political nation that elaborated new social and cultural values and transcended its linguistic, religious, and geographic differences. Fishbein celebrated this moment of the nation’s coming of age:

Paradoxically, the Yanukovych “gang” helped people out there in the streets realize they were united. It made them feel like they were human beings. Have you ever heard of anyone in Kyiv stepping on your foot and saying: “Excuse me, I’m sorry!” It was simply unheard of! Today, Kyiv has entirely changed. People are extremely polite. What is particularly fascinating is that we are talking about a million people in the streets. If someone pushed you accidentally, you would hear: “Oh, excuse me, Sir/Madam, I’m sorry!” People have become the paragon of politeness and good European manners. There is no criminality in the streets! We were so afraid and scared of provocateurs! They hung around, indeed, but their schemes did not work! Restaurants work and stores are open. There are no pogroms, no riots, no revolutionary sequestration anywhere in the city. The owner of the most expensive restaurant in Podil District, a distant friend of mine, comes to Maidan Square, takes dozens of people with him and feeds them in his expensive, fancy restaurant. The food – borscht, hot kasha, and meat! Every now and then you might see a lady in an expensive fur coat dragging a sled behind her with pots of hot food for the strikers! Russian-speaking, Ukrainian-speaking, Jews, Georgians, Eastern Ukrainians, Western Ukrainians—there is an amazing sense of unity. The feeling of love and unity is simply indescribable. Everyone is smiling, people’s faces are radiant and shiny with joy. There are hundreds of thousands, millions of them. This is not a mob. This is a nation.

Fishbein rejoiced in that birth of the nation: like thousands people next to him, he did not know how feeble, vulnerable, and dubious it might be. Back then, Fishbein found himself among those who peacefully took over the House of Trade Unions on the Maidan. Humor did not abandon him in the midst of the turmoil. He noticed how the dismissed head of the Trade Unions had run away from his office in panic, grabbing his sole and most precious artifact, a photo of prime minister Yanukovych. He was fascinated by a young female student who had arrived in Kyiv from the Kirovohrad region and, instead of staying with her aunt, slept in the Maidan square. He rejoiced in the mood of the rank-and-file riot police, ready to see his favorite political leader inaugurated. He could identify with each and everyone, because in the December streets of “orange” Kyiv, everybody was a messianic figure and Fishbein felt that he was one of the people. He told me back then, “I cannot tell you what it means to speak to this many people and to be heard by them. But I spoke—loudly and briefly, trying to be not one of those politicians….”

He did not need anything but that experience. He prefigured his return as one of his existential moments:

This spring, so sudden and bold,

The lilacs’ torrent, the lily’s warmth

The Easter harmony. Erase

The alien words from Paris, Vienna, and Vilna,

When it descends into your aorta a redeeming

“Thunder… the Dnieper… a return… the winds.”

Trans. by Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern.

He prepared and published a major poetic collection, “Early Paradise.” However, that paradise turned out to be too early both for the country and for him.

What followed was a decline and internal exile. It brought Fishbein from the heights of the Orange events to the bottom of, first, the Blue, and then, the Green reaction. Apathy came to replace fervor. Politicians whom Fishbein supported abandoned him as soon as they got to power. His desperation made him easily irritated; he pushed people away who loved him and helped him. His unconditional support of Ukrainian revivalism in all its forms, including UNA-UNSO, scared his Russian-speaking compatriots, and his unwavering commitment to Ukrainian language revival made him a persona non grata among many Russified representatives of homo sovieticus of Jewish origin.

As a betrayed prophet, Fishbein remained alone. He did not abandon his multiple attempts to protect the Ukrainian language against Ukrainophobia in all its manifestations. He ridiculed the idiotic Tabachnyk, minister of science and education,3 and his ilk, insisted in rare interviews on the redemptive quality of the Ukrainian language, a sine qua non of Ukrainian independence, and he corrected the Ukrainian morphology of his increasingly diminishing interlocutors. Russianisms unnerved him beyond measure: “zakhidniak,” not “zapadenets,’” he used to correct me.4 Fishbein went back to his Bukovyna-related Austro-Hungarian myths, to sublime experiments in Ukrainian metaphysical poetry in the style of Jorge Maria Eredia, and to his translations of Rainer Maria Rilke. Complaining about the Kyivan intellectuals who avoided him, he called himself in a private letter, “a virtual poet.” When the last volume during his lifetime, Prophet, appeared off the press, it became clear that Fishbein was the embodiment of only too familiar adage: “There is no prophet who is despised except in his town and his house” (Mark 6: 4).

Before becoming nearly blind, he entertained himself by playing on the computer in complete solitude, interrupted by long conversations with people annoyed by his desperate monologues. He took pictures from the web that he liked and connected them to the poetry he wrote. He then sent the results to those who were still able to tolerate his lamentations.

CHILDHOOD

… A friend is still alive, and I

Have not become a schoolboy. We

Have just imagined: Greece out there

Beyond the frames of winter,

And there is also Japan out there,

And out there Peru, and I

Will saddle yet a pony

And I will never die.

Trans. by Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern.

One day, googling references to himself and his writings, Fishbein came across one of the Ukrainian media resources. It reviewed an exhibition where WWII documents from the five main archives in Ukraine were displayed. There were also the papers of Yurii Yanovskyi and playwright Sava Holovanivs’kyi and—verbatim—“drafts of the poems of Moisei Fishbein, who was shot in Babyn Yar.”

Although in one of his poems he wrote that he had been killed in a 1916 pogrom, Moisei Fishbein was not murdered during the violence of the Russian troops in Czernowitz, or in Babyn Yar. He passed away as three-quarters of the country he loved chose to switch off their nation-building efforts. The extinguished Maidan had exacerbated Fishbein’s health issues and the coronavirus quarantine prevented him from using funds collected by his supporters to undergo a much-needed surgery abroad. Yet, his demise is more artificial than natural. It is man-made. A people who does not need its messianic figures tacitly kills them. Those who interview the murderers of Ukrainian-speaking boys and girls from the eastern regions, who destroy the feeble democratic institutions of Ukrainian culture, and who speak about pacifying the northern murderers,—and let’s call a spade a spade, those of us who speak Ukrainian in the streets of Kyiv while despising what happened in the country in 2004 and 2014—they all (and we all) participated in the slow but steady execution of one of the greatest modern Ukrainian poets. His only crime was a love of the Ukrainian language and the ability to pen Ukrainian verse.

Moisei Fishbein has entered the pantheon of Ukrainian classics, where he will be in conversation with Taras Shevchenko, Lesya Ukrayinka, Yevhen Pluzhnyk, Mykola Bazhan, and Leonid Kyseliov. Nonetheless, without his voice, his physical presence, and his vision of who we are and where we should direct our efforts, we have lost the sense of national redemption.

By YOHANAN PETROVSKY-SHTERN

Krytyka

|

|